Five Ways of Expanding Universal Basic Services

Questions of Cost (Core and Hidden), Eligibility, Scope, and Ownership

What are universal basic services?

In the last few years I’ve been involved with some policy and campaign work focused on ‘universal services’ or ‘universal basic services’. Simply put, this means services that are free-at-the-point-of-use, funded through general taxation. The most common examples are public healthcare, where at least some form of healthcare (such as hospital care) is free for all, and public education, where primary and secondary education are available free to all. Another familiar example in everyday life are public libraries, which can generally be joined and used without a fee. Examples of universal basic services in which I’ve had a particular interest include universal broadband (especially in the UK context), fares-free public transport (at the local level, in particular in Auckland, New Zealand), and universal dental (in the New Zealand context).

Increased attention since the mid-2010s

‘Universal basic services’ have received increased intellectual attention since the mid-2010s. There are many reasons why universal basic services have received increased intellectual attention since the mid-2010s. A major reason is that after the global financial crisis in 2008, following the Occupy movement and growing dissatisfaction with the political-economic order in a number of countries, there has been a resurgence of interest in social democratic and socialist political ideas. These ideas have provided a lens to understand the failings of the political-economic order, and a source of alternatives to that order. ‘Universal basic services’ offer a way of framing, and advocating for, a more expansive social state that works in the interests of low-income and marginalised people. (I say more about wording and limitations of ‘universal basic services’ at the end of this post.) Writers, policy-makers, and activists have been drawn to this frame at the same time that there has been a growing appetite for a more expansive social state of this kind, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and then as states grappled with how to respond to Covid-19.

Universal basic services also represents a variation on or alternative to ‘universal basic income’ (UBI), a policy proposal that grew in popularity in the late 2000s and early 2010s; some advocates of universal basic services are also supporters of a UBI, whereas others consider universal basic services to be preferable and a more urgent priority. (One argument is that universal basic services provide a stronger strengthening of collectivist solidarity, whereas a universal basic income risks entrenching individualism and providing an excuse to dismantle social services.)

A brief history of advocacy for, and analysis of, universal basic services

As a 2019 policy paper points out, universal basic services in practice have a long history - for example, going back to the militant trade union movement in Norway and the Black Panther Party in the US with its children’s breakfast programmes. The history could likely be traced back earlier, to Indigenous societies that agreed to provide the essentials of life to free for their communities. Universalism, in social policy in particular, also has a long history, especially in social democratic thought. The full history of the idea has yet to be written, and depends on how ‘universal basic services’ is precisely defined.

But the phrase was used more prominently in particular after the publication in early 2017 of Social Prosperity for the Future: A Proposal for Universal Basic Services, a University College London report which focused on seven basic services. The phrase was used by the UK Labour Party during the 2019 election, including in a policy paper, and also by trade unions in New Zealand as part of a campaign in the lead-up to the 2020 New Zealand election. Further analytical and advocacy work has followed, including a 2019 UCL literature review; reports, articles, and talks applying ‘universal basic services’ to particular contexts, such as Scotland; a book by Anna Coote and Andrew Percy (both of whom have been central in universal basic services analysis and advocacy); and a new UK-based organisation, called The Social Guarantee. Different projects and campaigns have used the phrase ‘universal basic services’ from a range of political perspectives; some campaigns have had different levels of ambition, with in particular a key political fault-line being whether universal basic services require public ownership of that service. I will not traverse here the attraction of ‘universal basic services’ as articulated by these various projects, other than to say that often universal basic services are said to reduce the stigma of means-testing, to be more efficient (by removing unnecessary bureaucracy), and to carry the political benefit of giving a broad public an interest in maintaining a service.

Extending analysis of universal basic services

These definitions, histories, and references are necessary to pay due respect to those who have developed the idea and practice of universal basic services - and to provide a background for the slightly more detailed points to follow. I recognise that what follows may be of particular interest to those sympathetic to universal services, or interested in this political project. The main purpose of putting some notes into writing is to develop tools of analysis relevant to universal basic services, which I hope will be strategically useful to those understanding universal basic services - and more importantly to those advocating for expanded universal basic services. I want to draw some distinctions that have seemed important in conversations about universal basic services (and I’m grateful in particular to those who have given me the opportunity to think harder about these issues and have been bold enough to use these concepts in campaigns). Drawing distinctions can sometimes seem pedantic, but I think it can help us to think more clearly about what we’re doing in our advocacy, and to make sure we’re not talking past each other. I hope it provides some tools that can increase the confidence of advocates arguing for more robust, more complete universal services.

Five ways of expanding universal basic services

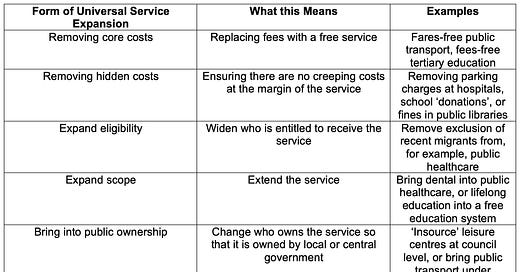

In particular, I want to draw distinctions between ways of expanding universal basic services. These are five axes of universal service expansion, or five different ways a universal service can be expanded or strengthened. I’ll then mention an indirect way of expanding universal services (via regulating third parties, like landlords and employers, to provide services) and outline two caveats or questions in closing. I don’t believe that these distinctions have been drawn already in the literature; if they have, I have not encountered them.

The first most common way of expanding universal services is to remove the core costs of a service: to make an existing costly service fee-free. Examples include making public transport free by removing fares (fares-free public transport) or removing fees on tertiary education. A key shift is achieved here where a service moves from being a fee-paying service to a service where cost is not a barrier to access.

A second, related way of expanding universal services is to remove hidden costs of a service that is notionally universal. Examples include removing parking charges in hospitals, removing school ‘donations’ in public schools, or removing library fines (a trend in New Zealand public libraries). A key argument for this move is that hidden costs can creep in, rendering what is meant to be a universal service a fee-paying service in practice. Removing hidden costs can guarantee a service is universal.

A third way of expanding universal services is to expand eligibility of a service or to remove eligibility barriers for services meant to be universal. I have in mind here in particular the way that non-citizens in some countries have recently (or for some time) been prevented from accessing public services that are meant to be free-at-the-point-of-use, for example in the New Zealand public healthcare system. I am aware of the arguments for such restrictions, but in my view they make a mockery of the claim that these services are in any meaningful sense universal. Shoring up the universalism of a service can also be done by removing such eligibility barriers.

A fourth way of expanding universal basic services is to expand the scope of a service. This can raise questions of how a service is defined. But examples might include extending public healthcare to include within its ambit dental services, or extending public education to lifelong education.

A fifth way of expanding universal services is to bring a service into public ownership, which can happen at a local level (‘insourcing’) or at a national level. Some might argue that this is not an ‘expansion’ of universal basic services but a shift in the type of service provision. In my view ensuring a service is publicly owned and controlled strengthens the universal service by removing the profit imperative of a provider, which may create an incentive for hidden costs to creep in or for eligibility to be restricted. This has the added advantage of shrinking the role of markets in our lives, possibly moving us all towards less of a ‘market society’. Examples would be bringing public transport into local government or central government control, insourcing leisure centres at a council level, or (in the New Zealand context) bringing ambulances into public ownership. There remain questions about what ‘public ownership and control’ mean here, which I have touched on elsewhere.

I’ve tried to summarise these five axes, or five ways of thinking about universal service expansion, in the table below:

Indirect forms of quasi-universal service provision

There is another indirect form of universal service provision: what might be half an axis, or half a way of expanding universal services. This is where third parties, such as landlords and employers, are required by state regulation to provide universal services. Examples might include employers being required to provide healthcare services, or landlords being required to provide basic broadband installation services (as is the case in New Zealand), or landlords being required to provide home insulation.

These are highly imperfect ways to deliver universal services: people without homes, or jobs, do not get the benefit of these services - and so there is no universal ‘guarantee’ of a service. The state does not provide the service directly, but regulates to ensure that some kind of service is provided indirectly. I mention it not to suggest that it should be part of an advocate’s toolkit; quite the opposite. I refer to it because it brings out some of the differences between universal services and related, but quite different ways, of delivering a service.

Of course, states can also regulate private companies to ensure some level of service quality is delivered, and sometimes this is given the label ‘universal’ (such as the ‘universal service obligation’ for broadband in Australia). This is quite different from the sense in which I have used ‘universal’ above, in that it does not remove the cost barrier to a service completely, but instead provides widespread access to a service.

Two caveats and a conclusion

Work on developing analysis of, and advocacy for, universal basic services will continue. I end with two caveats: one relates more to advocacy, the other to analysis, though both inevitably overlap if good advocacy is to be informed by sound analysis and analysis is to learn from advocacy. The first is that ‘universal basic services’ may not be the best label for what is being advocated for here. We could take issue with each of the words. Does ‘universal’ sound a bit cerebral, given the real-life benefits of full, community-wide enjoyment of the essentials of a good life? Should we limit this commitment to only what is ‘basic’ (a qualifier that evolves over time)? And if we describe these essentials of a good life as ‘services’, do we import or imply a market logic where we only get something in exchange for giving up something else?

The second relates to how universal basic services operate in countries where the state has a colonial history or for other reasons has questionable legitimacy. In these countries, and wherever there is widespread institutional racism in state institutions, advocates and analysts of universal basic services need to show due caution. Making services universal removes a cost barrier, but that will not be the only barrier to access to a service (as with healthcare in Aotearoa New Zealand). Moreover, foundational agreements in countries (such as Te Tiriti o Waitangi in New Zealand) may require that the state shares power with others in owning and delivering services. In New Zealand, Te Tiriti o Waitangi and especially the groundbreaking Matike Mai report may require that some resources (such as energy) cannot be straightforwardly brought into state ownership. In other instances, services might be publicly owned and provided - as with healthcare and education - but Te Tiriti o Waitangi (and Matike Mai) may require parallel structures, where some services are owned by and provided in the Crown kāwanatanga sphere, while others are owned and provided by Māori in the tino rangatiratanga sphere.

Universal basic services should not exhaust our demands or horizons. They are merely one part of a vision of a different state, a different society, and different world. But they are an important way to frame a set of transitional demands - one building block to lay down as we build foundations for a better way.

Thank you Max. I see such universal basic services as a building block to a refreshed “